You need very little of what is often suggested “`

This Guide will walk you thru the simple steps needed to create a nearly perfect snake cage – and explain why it is, in fact, nearly perfect! PLUS – you will have basically no maintenance of this cage. The waste produced will quickly cycle, just as it does in an aquarium full of fish.

What makes a great cage? If you believe much of whats out their online you would think it takes a lot of planning and money to create the best possible snake cage. The fact is none of that technology is needed, and much of it causes more problems than it helps.

Remember that the advice you see and read online is almost always offered by people trying to sell things. If not selling actual products, then they are selling their sponsors’ products, or selling themselves. Your animals are far from their priority!

I recently watched a YT video that featured a number of industry “experts” in a real time cage design competition. It was immediately apparent that the contestants had given zero consideration to the animal’s actual needs, but were simply pushing product – and themselves. A shameless self promotion masquerading as helpful guidance for the new keeper. Yuck.

When we think of good cage design we want to think about nature, and the micro-habitat that our species occupies within the broader ecosystem. Our animals have evolved over millions of years to exist in a specific environment. But so much of the current cage design paradigm we see doesn’t even acknowledge that environment.

Imagine for just a second that you are a rat snake, garter snake, hog-nose snake or other commonly kept species living in the wild. At the break of dawn on a spring day the temperature may be in the mid-60s, a heavy dew may lie on the grass, and the humidity is high. Its cool and damp in your world, and you’ve spent the night under a slab of bark, or a flat stone, secure and calm.

As the sun comes up on this spring morning you emerge from your cover and bask in the warm sunshine. As your body comes up to full operating temperature you begin your search for food. If you are lucky, you’ll track down a tree frog, a fence lizard or even a nest of baby mice.

After feeding you need warmth and security. You find a rock pile warmed by the sun, or curl up under dried grasses along the forest edge to digest your meal. It is warm and dry all through the day. The warmth lingers in the rocks or under the grasses, allowing you to stay warmer than the surrounding air well into the night.

In this simple scenario we see a wide range of temperatures and humidities in the course of just one day. We see the snake has adapted her behavior to the wide ranging conditions too. We see radiation in the form of UV and (more important in the snake’s case) near infra-red.

The snake has access to 90% humidity under the rocks, 60% humidity under the grasses or leaves, or 30% humidity basking in the sun – all within a few feet of each other!

The snake has an equally big thermal gradient. From the mid-60s under the stones, to the 70s and 80s under the leaves or grasses, all the way thru the 90s basking in the sun.

In order to provide care that responds to our snake’s needs we need to provide these big gradients. They are adapted to the conditions and they know how to take advantage of them. Full of food they will select the warm, dry areas. Getting ready to shed they may spend days under cover, safe and secure in a high humid environment.

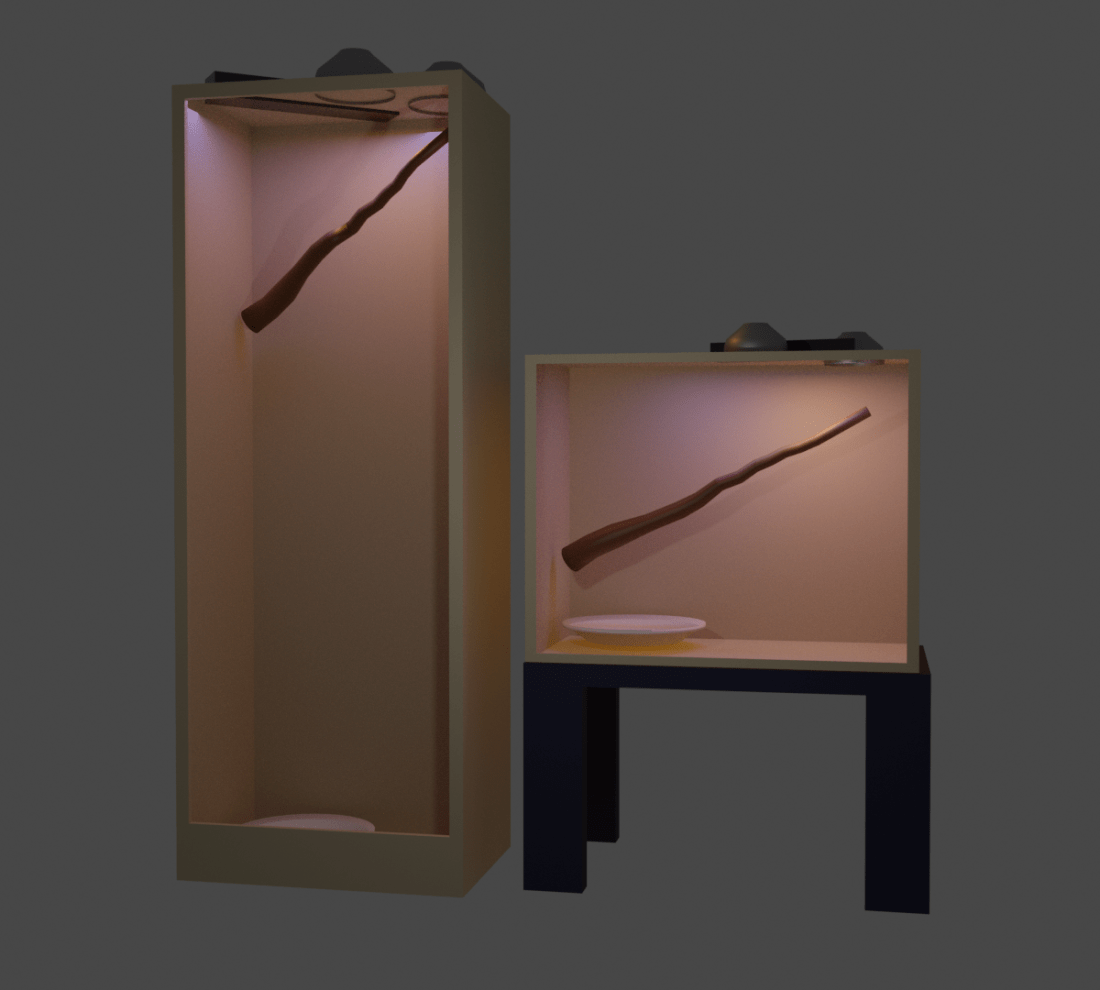

So how do we manage all these variables in a small enclosure? Thankfully it is neither complicated nor expensive. The entire set up takes only a few minutes once you have gathered the materials!

Believe it or not, one of the best choices for a snake cage is a glass tank. People get confused about this for a couple of reasons. Some suggest the clear glass makes the animals nervous. This is not often the case, but can be remedied by taping paper or some other cover on the back and sides.

Others suggest the glass transmits too much heat. But the more heat that is lost thru the cage walls the better! We are not baking cookies! This is not an oven. The temperature gradients we want to create depend on heat being quickly dissipated, which is why the screen top is so perfect – we *want* the heat to rapidly escape thru the top of the cage.

One of the biggest design flaws in commercial cages is bad ventilation. Often they have vents clustered up at the top sides or the back with no option for the inflow of cooler, fresh air. This is a *critical flaw* and is one of the reasons I have never purchased a commercial cage and never will.

Substrate

So with our basic tank set up, we add a deep layer of a good quality potting mix. I use Miracle-gro because in my experience it offers the most consistent high quality. Potting MIX is key here. DO NOT use top soil which can contain pathogens and is NOT suited for containers like our vivariums. It actually states this on most packages. Do not buy top soil, or garden soil, or raised bed soil and then amend it with other stuff. If you created the most perfect ABG (Atlanta Botanical Garden) mix it would be no better, and probably much worse than quality potting mix.

Do not buy substrate from the online sites or herp shows or pet stores. Ive tested these products and they range from terrible to passable. But none are as good as potting mix. (Note that potting mix can be mixed with up to 50% *coarse* sand, not fine, or play box sand. You want drainage and the coarse sand will drain much better than the fine sand.

Do NOT add a drainage layer! No bigger wrong headed, waste of money has ever been invented.

The only learning curve to this set up is managing substrate water content. The substrate needs to be wet well, then allowed to dry down to nearly dry. The lowest layer of the potting mix will tell you when to add more water. And when you do add water, add plenty. For example a 20 gallon long aquarium with 3-4 inches of potting mix may need 3 gallons of water poured in every 3-4 weeks.

Rocks

Rocks are not required but provide many benefits. Snakes love rocks. They seem to understand they are safe in a rock pile. In nature we often find snakes in and around rock piles.

Rocks absorb heat from our overhead lamp and dissipate it when the lamp is turned off. This provides a gentle heat gradient even after lights out. As important, rocks provide the rough, solid surface snakes need to shed. A smooth sided cage can seriously injure a snake as it pushes hard trying to start a shed.

The most important thing about rocks is that they have to be set directly on the cage floor, and set their securely. Otherwise a snake may burrow under a rocks and have it collapse on top of them. Wedge them in good so the snake cant disrupt them.

Forest Litter

Some sort of forest litter is also critical. It seems simple but it plays a huge role in the creation of the environmental parameters in our vivariums. I use dried leaves (collected from a nearby state park as soon as they fall so they don’t collect bugs and mold), or hay or straw from the farm store, or even dried grass from the mower.

The reason this forest litter layer is so important is because it creates an all important humidity gradient by trapping the moisture evaporating from the potting mix. Humidity under the litter can be 80 or 90% while humidity a few inches away under the basking light can be 40% or even less.

The other reason this layer is important is because it allows the snake to thermoregulate without being exposed. Admittedly this is more important for some snakes than others, but for many species – especially when young – it is very important.

A snake has to thermoregulate to be healthy. They have to be able to choose appropriate temperatures for digestion, shedding, metabolism and reproduction. The old 2-hide system with one hide on each end is a bad substitute. With this layer of forest litter the snake can micr0-manage it’s body temps and its humidity very similar to how it would in nature.

Climbing Branches

In captivity even thoroughly terrestrial snakes will climb. Partially just trying to escape, but branches offer a third detention to their thermoregulation. They also offer the snake more shedding assistance, and this can be important depending on species your keeping.

Screen Top w/ Clamps

Screen tops are erfect for snakes because they provide the temp gradients and the fresh air all herps need. Note you will not need to cover the top even partially to increase humidity. Remember our potting mix substrate will be providing the humidity – and will be doing it in a natural way that the snake is adapted to. In nature when snakes need higher humidity the go to the forest litter, under surface cover like rocks, logs and leaves.

Clamps! I’m embarssed to say that I have on more than one occasion walked away from a snake cage secure in my belief that the occupant can in no way get out of its tank, only to find later that it has! These clamps are a PIA and I wish some innovative changes would be made to them, but they are a lot less of a hassle than searching for a lost snake. And to be honest, they are a lot less hassle than the stack of books or bricks we used to routinely use to keep lids tight.

Another critical element of good cage design is over head incandescent / halogen lamp. Not ceramic heat emitters (their heat does not radiate down, it floats up!), and not radiant heat panels (they have the same problem).

Incandescent bulbs produce the same warming radiation that the sun does. It penetrates the snake’s skin and is distributed thru they animal via its circulatory system. The radiation from ceramics and RHPs does not penetrate the snake’s skin. It is an un-natural, and unhealthy way to provide anything other than background or ambient heating.

Not that you dont have to buy the expensive bulbs and reflectors sold at pet stores. These better quality reflectors are sold for raising chicks at the farm stores. You might even try buying the 150 watt heat bulbs sold there – but make sure you have a dimmer to dial them back.

Notice there is also no reason to (almost) ever buy a thermostat. The $3.00 thermometer un the photo is more than adequate to establish the right warm side temperatures. Wireless dimmer / timers can be bought now for not much money, and they are a much better investment than the thermostats.

Here is a link to the digital dimmer / timer:

https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0BXP8QL52

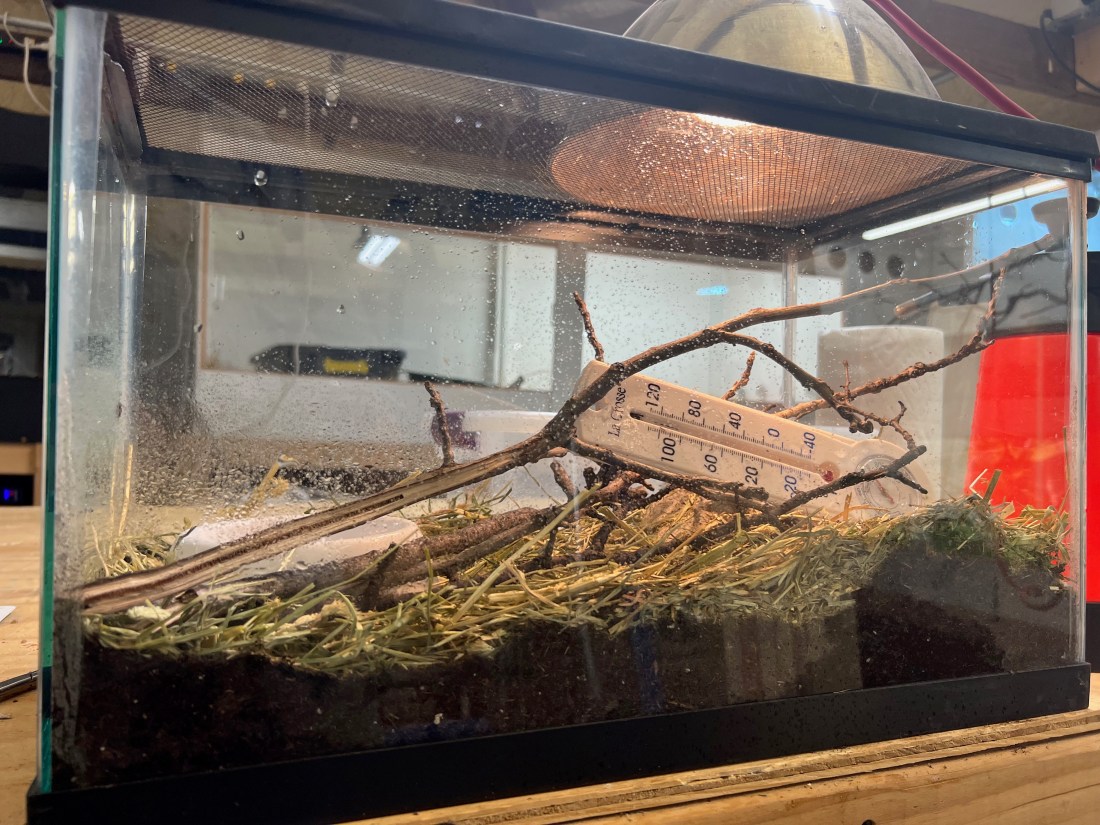

So here is a look at your tank all set up. Notice the snakes can hide under the water bowl at the cool end. Humidity under the bowl will stay quite high – easily 80%. The temps will go up and the humidity will go down as the snake moves from the cool water bowl to the warm rocks. And it can find both security and perfect environmental parameters under the forest litter anywhere in between.

The branches rise up closer to the warm light, so add even warmer options for the snake.

All that is left to do is add your snake(s) and start your observations. You will want to watch and learn from your animals now. where do they hang out in the vivarium? Where do they avoid? Double check your temperatures and your moisture levels.

In a well designed anclosure like this there will be times when you wont see your pet. This is a good thing. It means she is happily snug down in the substrate, not stressed out, crawling around searching for better conditions. After the snake feeds it may disappear into the rocks to digest for a few days. When it enters a shed cycle it will certainly head into the cool, humid substrate to properly prepare for shedding.

And when it sheds, it will be a perfect or nearly perfect shed! A good sign that you have done everything right!

And here is some good news. Once you get these design parameters down, you will know how to make great cages for many species of many sizes – from baby garter snakes to big indigo snakes, and many in between.

And here is the amazing thing. You can design and build this enclosure for a tiny fraction of the cost of the poorly designed cages we so often see online. There is simply no need for the expensive bits and pieces that are often suggested by those who make money from their sale. There is nothing you could buy at a pet store or online that would make this design better for your animals, although obviously you can add whatever aesthetic elements you want, as long as you dont alter the environmental parameters provided by this basic design.